Every Adventure Game Fan Needs To Know About Roberta Williams

Published

| Last updated

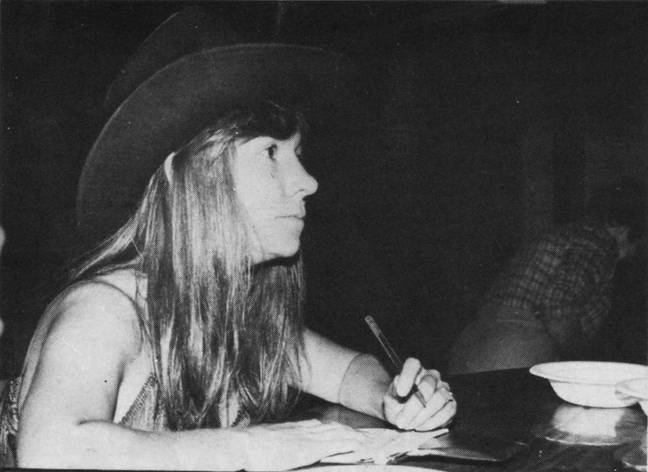

Featured Image Credit: The On-Line Letter, Public Domain / Sierra On-Line

The graphical adventure genre might not quite be the stuff of AAA gaming popularity in the 21st century, but its influence continues to be felt. Modern titles like the Life is Strange series, Telltale’s narrative releases, Oxenfree and its upcoming sequel, Gone Home and Firewatch and What Remains of Edith Finch, and even action-adventure affairs and RPGs with interactive environmental puzzles and branching dialogue options owe a degree of debt to point-and-click experiences on home computers of the 1980s and ‘90s, and the more text-based graphic adventures before them.

Some names of that era remain iconic: The Secret of Monkey Island, Grim Fandango, Beneath a Steel Sky, Sam & Max Hit the Road. And then there’s the games of Sierra On-Line - without which, arguably, the graphic adventure genre never even happens. And you can’t talk about Sierra On-Line - previously On-Line Systems, later Sierra Entertainment - and its seminal King’s Quest series without focusing on the designer behind its breakthrough releases, and much of what followed: Roberta Williams.

Born and raised in California in the 1950s, Roberta Heuer grew up with a vivacious imagination and an appetite for fantasy stories. She married her husband, Ken Williams, when the two of them were young, and when she wasn’t dealing with the demands of the couple’s two kids, Roberta would play with Ken’s Apple II computer. She enjoyed text adventure games - games in the vein of 1976’s Colossal Cave Adventure, and 1977’s Zork. (“I just couldn’t stop,” she said of Colossal Cave Adventure; “It was compulsive. I started playing it and kept playing.”) These games used text commands inputted on a keyboard to progress - “walk west”, “use lamp”, or shortened versions of them - and their worlds were written into existence rather than illustrated on screen. All you had as the player was a wall of text, and the boundless possibilities of your mind’s eye.

Now, if you grew up in the UK in the early or mid 1980s - and I know a lot of you didn’t, because I know our demographic, but bear with me - you might recall a game you played at school, on old BBC computers, called Granny’s Garden. The aim of the game was to save some kids and avoid the clutches of an evil witch, and it was played by typing in simple commands - like the aforementioned text adventures. However, Granny’s Garden also featured illustrations - crude, sure, but they brought a more focused sense of place to each playthrough. Granny’s Garden was a graphic adventure, and quite probably wouldn't have played the way it did without Roberta Williams’ work a few years earlier.

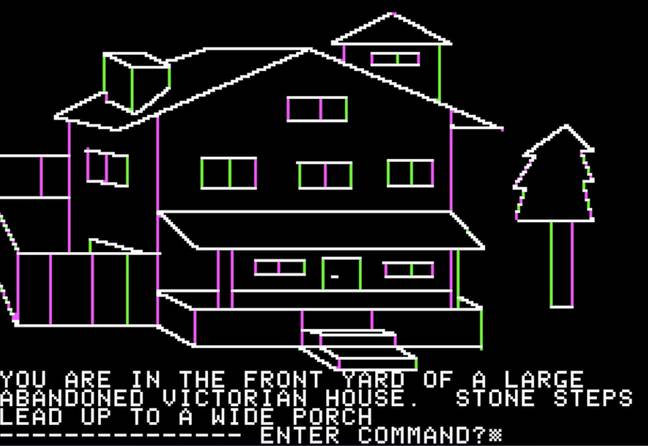

In 1979, Roberta and Ken founded On-Line Systems, a game development studio and publisher. The company’s first release was 1980’s Mystery House, a murder mystery set in a spooky mansion designed and written by Roberta with programming by Ken. It was released for the Apple II computer - makes sense, given what hardware the pair had at home - and was the first-ever text adventure game to feature pictures of the environment or situation the player found themself in, each of them drawn by Roberta - from the outside of the building to each room and its occupants (living, or dead). That all sounds like a lot of technical input, and a lot of responsibility, for Roberta - who didn’t set out to pioneer a genre with Mystery House, but simply made the game she and Ken wanted to, as On-Line Systems’ debut. It was more a hobby project than a commercial venture - but the game sold 10,000 copies on its first run, via mail order. Doesn’t sound like much today, but it was huge for the couple and their nascent business.

“I knew people would like [Mystery House] in those days because it was really different and new, but I didn't really think it would start a company the way it did,” Roberta told ROM magazine in the summer of 1984. Later, in 2006, she spoke to Adventure Classic Gaming about what she prioritised when it came to designing her games:

“What is the story? Who are the characters, especially the main character? What is he/she trying to do, i.e. what is the quest? In what sort of 'world or land' is this game going to be played? In other words, I always thought first of the story, characters, and game world. I needed to understand those before I could even think about any game framework, 'engine,' or interface.”

So while the release of Mystery House represented a significant progression for adventure gaming, its genre-founding style was born more from necessity, to be a vehicle for the characters and story, than any urge to progress the how of our interactive play. More titles followed - including Wizard and the Princess, learning on Roberta’s love of fantasy books; Time Zone, a journey through history that came on a whopping six double-sided discs; and The Dark Crystal, a graphic adventure adaptation of the Jim Henson movie of the same title - before, in 1984, the developers now known as Sierra On-Line released King’s Quest, and adventure gaming took another giant leap forwards.

King’s Quest - its title later revised to King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown in 1987, and a remake of 1990 bore the moniker of Roberta Williams' King's Quest I: Quest for the Crown - was the first graphic adventure game to feature animated visuals alongside its text gameplay. You can see yourself in the game, your character on the screen, and move them around the world - something that seems a given today but was all new for adventure games when King’s Quest released. The player’s character, Graham (yes, really), will stoop to pick things up, pass by environmental objects and become briefly obscured by them, open doors and wade through water - on-screen interactions that were revolutionary at the time.

King’s Quest’s colourful and lively visuals were built on a brand-new engine, the Adventure Game Interpreter, developed by Sierra and used right up to 1989’s Manhunter 2: San Francisco, a post-apocalyptic adventure published but not made by Sierra. Other games to use the engine, outside of the King’s Quest series, include 1987’s Police Quest and 1988’s Wild West-set Gold Rush!. Roberta Williams led the development of the AGI, and both designed and wrote King’s Quest - and while she obviously played a part in another huge technical achievement, it was the story side of her work that she remained most passionate about.

“I am most proud of the development of the characters as personalities that game players could relate to and care about,” she told Adventure Classic Gaming. “A lot of thought was put into making the King's Quest world as beautiful as possible, as easy to navigate and communicate with as possible, and as engaging and entertaining as possible. Trying to come up with mind-bending puzzles and brain-twisting plots was never something that I strived for, although, I believe that many designers of games and/or adventure games make their games more complex than they need to be.”

Insert your own rubber chicken remark, right about here. Williams and Williams - and Sierra On-Line, rebranded to Sierra Entertainment in 2002 - would go on to make several more King’s Quest games, alongside developing and publishing countless other titles. Roberta was last directly involved with the series in 1998, acting as co-designer on King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity, which used a point-and-click interface and still starred Graham - now a king of his realm, albeit one turned to stone in this game’s storyline. And before that came a very different kind of game, albeit one equally iconic in adventure gaming, to bear Roberta’s design input: 1995’s Phantasmagoria.

---

"I loved working on Phantasmagoria and consider it one of my best games. If people still love it and are talking about it, that fact pleases me more than you can imagine."

- Roberta Williams reflects on the impact of her 1995 point-and-click horror game

---

Roberta had always wanted to do a properly scary game. “I would like to try and write some mystery and suspense, and would really like to write a scary adventure game,” she told ROM in 1984. “Scary, not in the sense of gory, but suspenseful, similar to the Alfred Hitchcock style.” But the point-and-click meets live-action full-motion-video gameplay of Phantasmagoria was very gory in places, with Billboard noting its “bloody special effects interspliced in trusty scare-flick fashion with daubs of flesh and hints of sex” in its review. GameSpot felt the violence was over the top, but PC gamers lapped it up: the game grossed 12 million dollars in its first week on sale, and by March 1996 its worldwide sales had passed 600,000 units.

Watch the GOG release trailer for Phantasmagoria, below…

Loading…

Phantasmagoria was a labour of love for Roberta. Its story was based on a 550-page script she had written. She faced resistance, including from her own husband, to some of the game’s content - as well as the gore, Phantasmagoria features a rape scene which Roberta insisted was vital to the story - and oversaw the casting of every one of the game’s 25 actors. It took a team of over 200 people to bring Phantasmagoria to life, but at the centre of the process throughout was one person: Roberta Williams. In a 1997 email interview, she reflected on the experience, and what she’d taken away from the making of Sierra’s most ambitious (and expensive, at a budget of $4.5m) project ever.

“I haven't read as much internet reaction about Phantasmagoria as one might think,” she said. “I've been very involved with King's Quest: Mask of Eternity and have not focused much on Phantasmagoria lately. I can say though, that I loved working on Phantasmagoria and consider it one of my best games. If people still love it and are talking about it, that fact pleases me more than you can imagine.”

And so here we are, in 2021, still talking about not only Phantasmagoria, but also Mystery House, King’s Quest and the role that Roberta Williams played in evolving adventure games, ultimately taking them towards where we find them today: multiple-path-featuring experiences full of rich dialogue and memorable characters. Her work has been invaluable in video gaming’s development of titles, series, and whole franchises that are, in Roberta’s own words, “for people who are not necessarily great at playing computer games, or who just want to relax and explore a story as opposed to playing a relatively complex ‘game’ game”.

Roberta effectively retired from game development in 1999 (or, did she?) but continues to give interviews on the highs and lows of Sierra On-Line and its incredible output - her incredible output. But she was never one to dwell upon successes, to rest on any laurels. In early 2021 she spoke to Adventure Gamers, saying: “I’m a person who always looks ahead… [when a game shipped] it was like a wizard came and sucked it out of my brain, and it was gone. And it was a relief. I just didn’t have the desire to go back and see [the older games] again. I was always ready for the next, and that’s the way it’s always been.”

That next, in 2021, is Roberta’s debut novel, Farewell to Tara, available now - but it turns out that game design isn’t totally off the table, either. Roberta and Ken were said to be working on a new game, a “Sierra-flavoured” title called The Secret, in the summer of 2021; but there’s been no update on it since. Could 2022 be the year of Williams' comeback? Certainly, a Sierra-like game wouldn’t be out of place at all in the contemporary adventure landscape, finding itself in good company alongside so many other projects created by people directly inspired by King’s Quest and its ilk. And Granny’s Garden, obviously.

This piece is part of a series profiling influential game creators, true masters of style, and their key works. Read previous entries: Fumito Ueda (Shadow of the Colossus), Amy Hennig (Uncharted), Hideki Kamiya (Devil May Cry), Hideo Kojima (Metal Gear Solid).

---

This editorial content is supported by Philips OneBlade. Philips is committed to providing products that fit into every individual's life, to suit every personality's idea of style. Every one of us is unique, and every one of us feels comfortable and confident in different ways - and the flexibility of Philips OneBlade ensures that anyone can express themselves in a way that's all about them. Find more information here.

Topics: Retro Gaming, Opinion, Philips, PC