Words: Stephen Wilds

As someone who is legally blind, I've often had to fight through older video games that didn't work well with my vision. I would skip entire sections, get a friend to help, or give up on adventures that had too much reading, gruelling sniper battles, or items I couldn't spot.

And the majority of gamers don't realise how many people who share their hobby are disabled - be that visually, through hearing loss, or they experience physical or cognitive issues that prevent them from playing in the same way as non-disabled peers.

Advert

According to research from the charity AbleGamers, up to 46 million gamers in the United States have some sort of disability that affects them being able to play video games. And that figure may actually be on the low side, as it does not take into account aging gamers. Mobile games developer PopCap estimates that around 20% of the player base is disabled, while 10% of all male gamers are (red/green) colourblind. In the UK, some 13.9 million people have a disability, and research from Muscular Dystrophy UK found that one-in-three gamers has been forced to stop playing due to their disability.

And these statistics really aren't new. They might be more visible, but they're the quantitative representation of a long-term issue. Though it's only recently come to the forefront, with several features in the gaming press and beyond, the subject of accessibility in games has arguably been an ongoing one since the medium's very beginning.

There were signs of it with early arcade machines and home consoles, well before the Nintendo Entertainment System swept the US, and subsequently the world. Some games had difficulty levels, options to use easier controls, and there were even eye-tracking devices to allow characters to be moved without a joystick.

Advert

But these advancements were mostly being made by small developers and hobbyists who were overcoming personal issues or trying to help those close to them, and rarely by the major gaming companies. Much of what was commercially available was either too expensive for the average consumer, or simply not known about. Many players took matters into their own hands, deciding that if game developers wouldn't make their products more accessible, the users would - and that mentality would continue throughout the decades.

Unfortunately, there is a difference between hardware and software accessibility, and some things can't be changed unless the developers make it happen. PC gamers have always had a leg up on making games easier to play, with created mods and customisable interactivity through keyboard and mouse, but the console market has always been an easier point of entry into the hobby for most.

---

Advert

I began my own research into this subject wanting to talk about accessibility in previous hardware and console generations, in the hope of showing off older games that catered for a diverse audience. But I was surprised at how few titles had any options that would significantly affect gameplay for less-abled gamers.

Options were so scarce on my original PlayStation and Xbox, back when they were cutting-edge consoles, that I stopped looking. And addressing them now, it's no wonder. Accessibility settings just weren't being built into the software at the time. Many of the functions that did assist disabled gamers were accidental or intended for something else, with any increased playability ultimately a coincidence rather than a feature.

This isn't to say that nothing was being done for gaming as a whole before then. Bertie the Brain, built in 1950 and considered to be one of the first video games, featured adjustable difficulty levels to make its tic-tac-toe against an AI approachable for everyone. The Atari 2600 offered several games with Special Feature modes (denoted by teddy bear stickers on the carts) designed for younger children that would slow the game down or alter gameplay, making them more manageable.

Advert

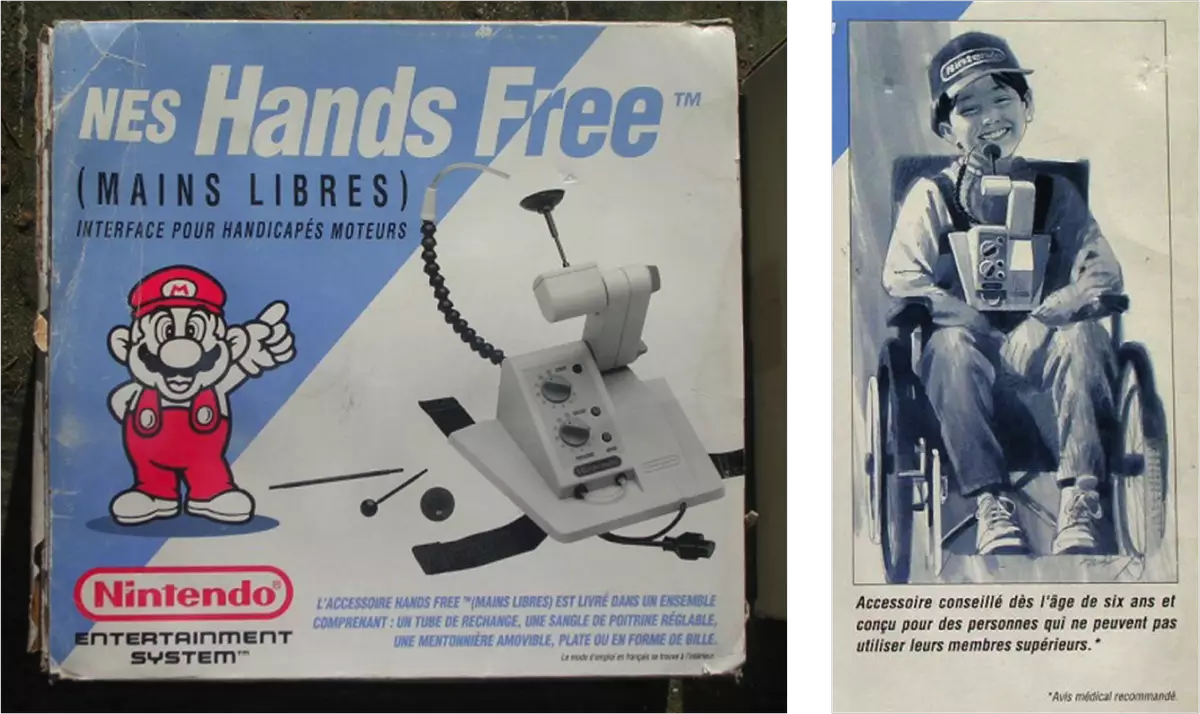

In the late 1980s, Nintendo would create its own Hands Free controller, a NES-compatible device strapped to the chest that allowed someone to sip or blow air into a straw that could be maneuvered with the tongue for movement. But not many knew about the device, as it was only available via Nintendo's own customer service line, and it wasn't cheap.

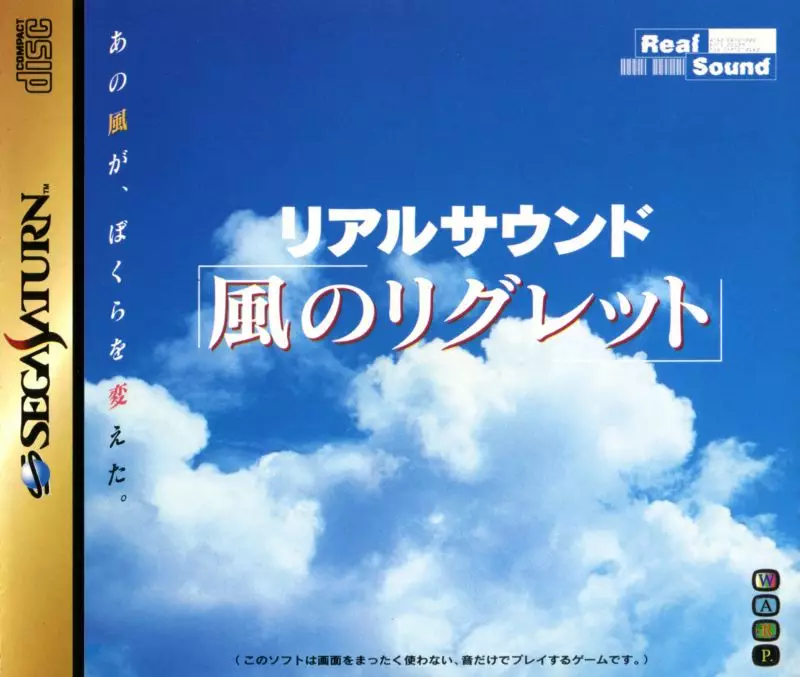

A few years later, in the mid-1990s, the SEGA Saturn opened itself up to many disabled gamers by requiring each title to have button remapping. It even had one title specifically designed for blind players, a kind of interactive radio drama called Real Sound: Kaze No Regret. But unfortunately it remained a Japan-only release, even for its later Dreamcast port.

It's tough to make a product that suits all impairments, and making different ones for each disability issue can be costly - but everyone wants to play, and most developers want that, too. Companies believe it benefits them to work with the disabled, and Mark Barlet, founder of AbleGamers, agrees. "There is money being left on the table," he told USA Today, adding that many disabled people have expendable income.

Advert

But this isn't all about money per se, as several developers expressed the desire to have more players experience their games. There is a notion, misplaced though it is, that making games more accessible dilutes the intended state of the creator's vision, taking away from the original ideas and struggles. We see this every time the Dark Souls difficulty debate flares up.

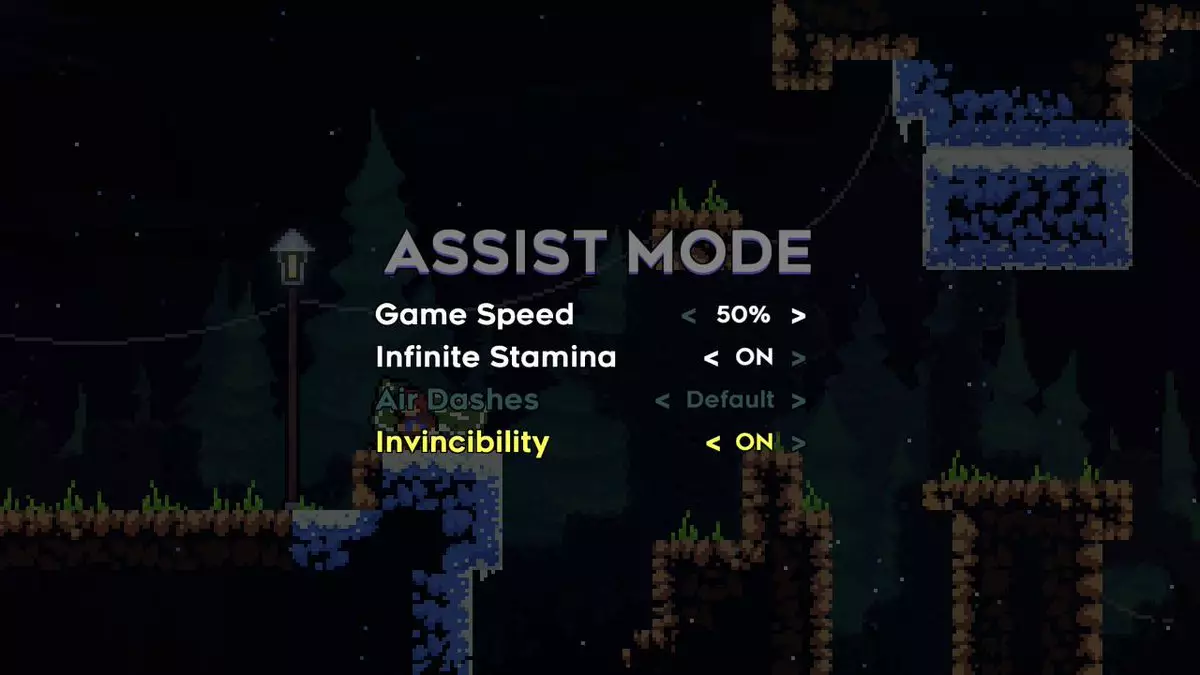

But many popular titles have started to add accessibility options, and are still praised for their testing content while also selling well to those who otherwise couldn't enjoy them. A case in point here is Celeste, a game I'll come back to.

Game developers don't feel that addressing accessibility hurts the projects they are making, but many of the studios do run into problems making sure they are put in. According to journalist Jason Schreier, in an article for Wired from 2011 which still rings true today: "Even if they can convince a game studio to consider closed captioning or button remapping, those features will likely be the first things to get scrapped when deadlines loom and developers start working 10- to 12-hour days to finish games."

Related: watch how a blind gamer plays fighting games

Having the makers of the games see the benefit in these options, and be willing to make them a reality, is incredible. But that isn't the end of the struggle, as accessibility options making it into the final build, the released product, is a long road.

The YouTube channel Extra Credits may have said it best in 2017, when they stated: "Accessibility in games is sort of in Wild West territory right now. The rules and the guidelines are still being written and the means for their creation are still in their infancy." That is still true a few years later, but things have finally started changing. "The industry in the last three years is 180 degrees from where it was before," says Barlet, who adds: "Accessibility isn't a dirty word anymore, and it was at one point."

---

I spoke to Ian Hamilton, an accessibility specialist and consultant, about the history of accessibility in the industry. He told me that in 2008 Ubisoft began introducing more mandatory requirements across its games for subtitling and epilepsy triggers, explicitly for disabilities. Elsewhere, World of Warcraft, one of the world's largest MMOs, added a colourblind mode in 2015 - no doubt a hugely helpful feature considering the number of players the game has boasted over the years. And in 2016 EA established an Accessibility Division, whose efforts have greatly improved the experience of their sports titles for players.

Xbox released their Co-Pilot mode in 2017, allowing for a second player to aid a disabled player, with two pads working in tandem to control one avatar. The company took a huge step forward a year later with their Adaptive Controller, which provides some of the most freedom for mapping and fitting customised inputs to an individual. It works for Xbox, Windows PC, and someone even made it work for Switch. This controller has been praised as one of the greatest advancements for players with physical disabilities, and is made even better with Logitech's Adaptive Gaming Kit, which adds buttons and triggers to the peripheral.

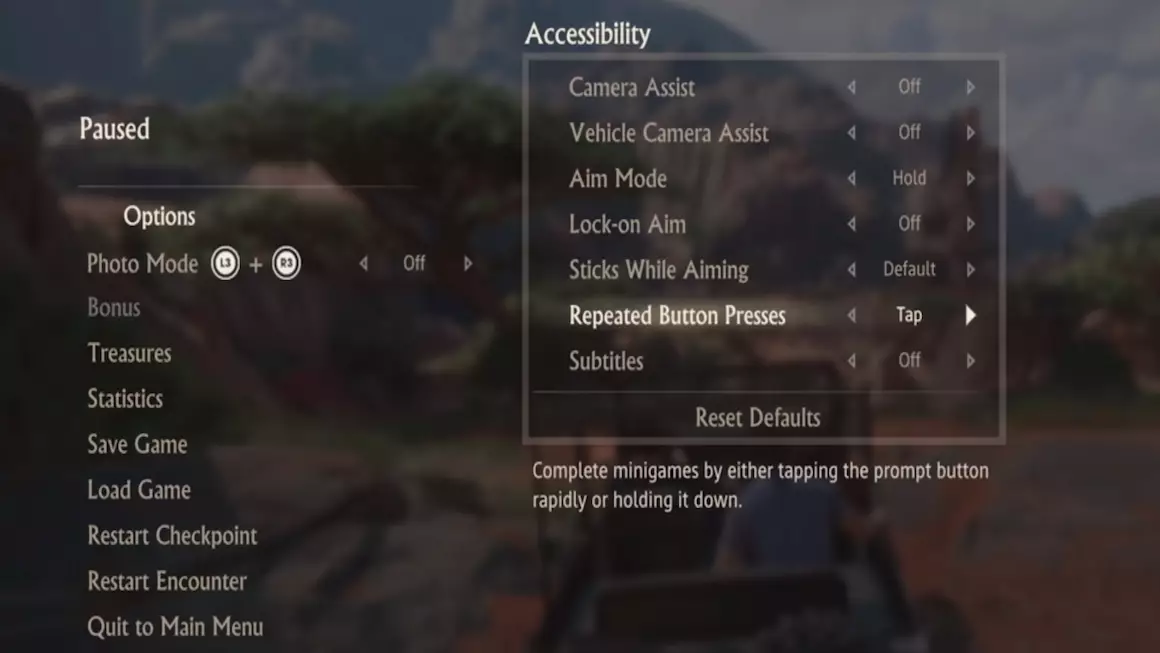

Many current-gen titles have stepped up to the plate, making themselves more inviting for as many as possible. The Uncharted series, made by Naughty Dog, went out of its way with its fourth installment, 2016's A Thief's End, including a wealth of accessibility options following a conversation with disabled gamer Josh Straub, who couldn't finish Uncharted 2 (and subsequently founded DAGERS). Borderlands 3 allows players to scale their entire UI, to the extent that it can cause text to fall off of the screen. Marvel's Spider-Man has a slew of settings for visual impairments with large subtitles and audio cues, while Far Cry: New Dawn incorporated indicators to help wasteland warriors determine directional or radial sounds.

Shadow of the Tomb Raider upped its subtitle game by adding more closed captioning, like listing who is speaking and having an option for each speaker's text to be shown in a different colour. Lara's latest adventure, released in 2018, also mastered dealing with difficulty modes by making combat more manageable for the disabled without altering the complexity of its environmental puzzles. On Nintendo Switch, Mario Kart 8 Deluxe makes driving easier by having an auto-accelerate feature, letting players focus on their steering and shell-tossing.

One of the biggest recent games to really highlight accessibility advances, Celeste, is ostensibly a challenging platformer - but its options let players adjust nearly everything concerning movement and more, allowing them to focus on the tremendous story by offering unlimited jumps and dashes, or full invincibility. Gears 5 was also celebrated in 2019 for its incredible array of options, including small details incorporated into the core gameplay and combat, like making bullet trails easier to follow for low-vision players.

New, smaller games like Way of the Passive Fist - an arcade brawler - was designed from the ground up with multiple types of accessibility in mind, and severely disabled players can now play Minecraft just using their eyes with new software. All of these are welcomed and amazing features, but they aren't everywhere and many commenters in the media, like the AT Banter Podcast, still say that accessibility is just now finding its initial footing in the gaming medium.

For many though, the industry still isn't doing enough, and remains stuck in that Wild West period. "That applies across the board," Hamilton says. "There aren't really any games that do a good job of accessibility yet - it's early days. Even games like Celeste, Gears 5, Eagle Island and Spider-Man are barely scratching the surface." But there is progress, where for a long time it seemed like there wasn't. "Many of the current trailblazers are still just starting to implement [accessibility options] a little bit late in development," Hamilton adds, "and they always say the same thing: 'man, if only I'd thought about this (accessibility) earlier.' In their next games, they can think about it earlier."

---

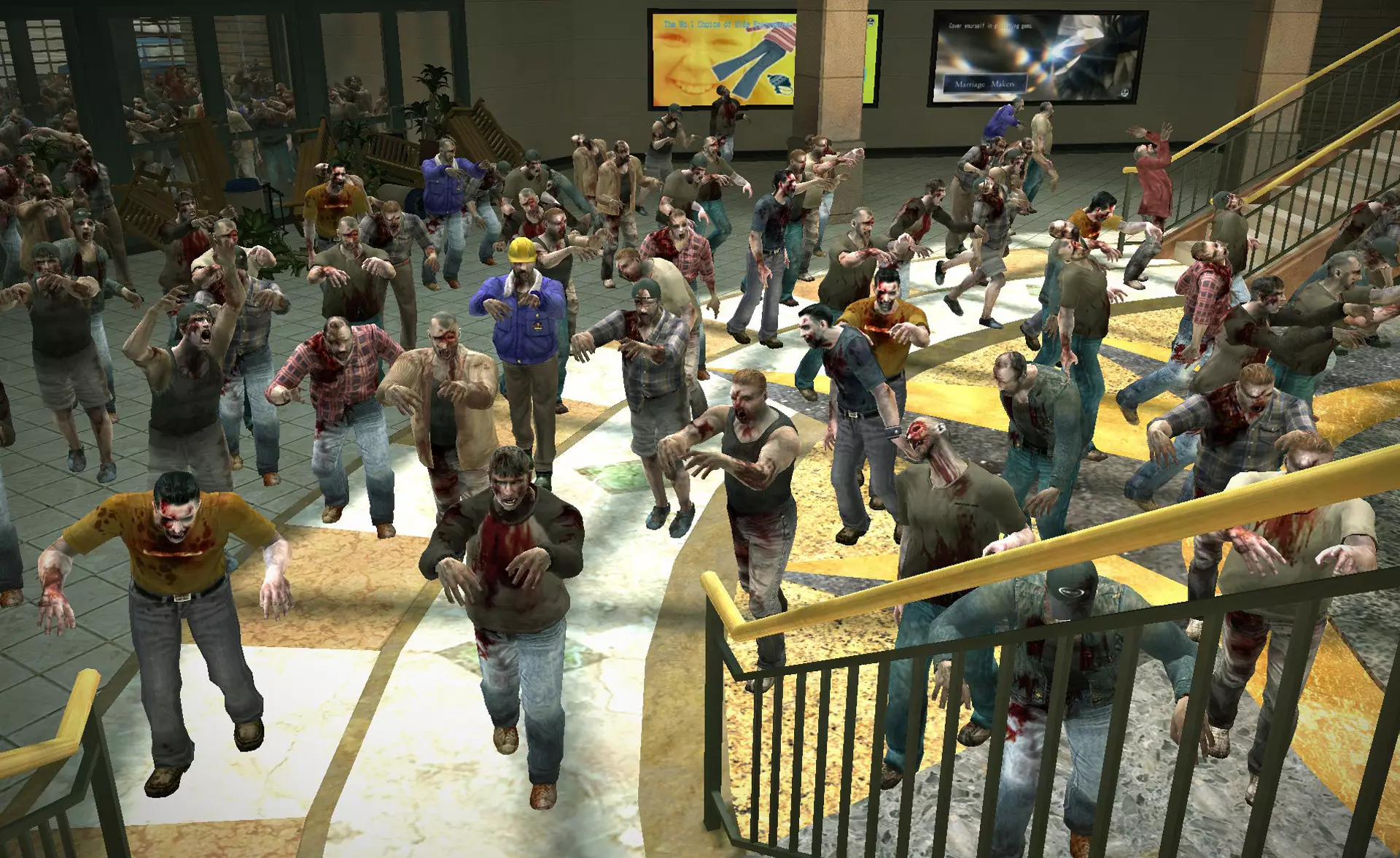

Rewinding a generation, the arrival of the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 introduced new HD technology to mainstream gaming. But this also created a problem for a while, as developers figured out how to work with text size. Dead Rising, an early 360 exclusive, had an infamous issue with non-HD televisions, on which its minuscule text couldn't be read clearly (if at all). But even when played on an HD screen, the game was still hard to follow, and it was a problem that was never fixed by Capcom.

The original BioShock had some fun mini-games, but they were unplayable for those with certain types of colour vision deficiency. And to this day, there remains a lot of games that do offer accessibility options, but do so poorly. When DOOM 3 was released in 2004, it didn't come with any sort of closed caption options, despite some sections relying heavily on audio cues. When it was released on Switch in 2019, it was still missing this feature. The newer DOOM of 2016 makes improvements in terms of its subtitling, but confusingly offers a mode that alters the player's view to show Mars as someone who's colourblind would see it, while not providing an actual colourblind mode for genuinely colourblind players.

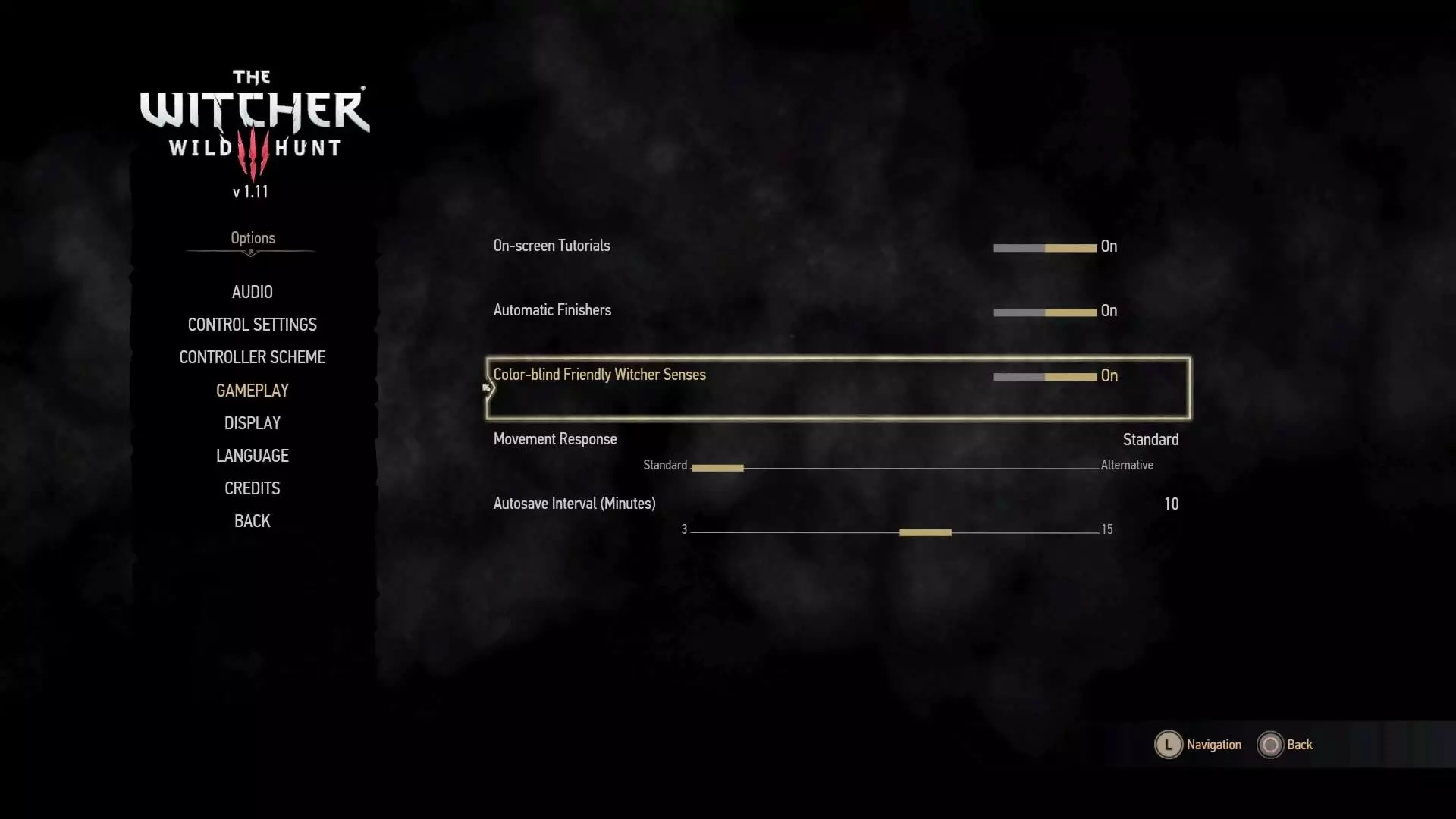

The Spiro Reignited Trilogy of 2018 was originally released without any subtitles at all, but was thankfully patched later. The 2019 remake of Resident Evil 2 was virtually unplayable for deaf gamers, especially when the hulking, unstoppable Mr. X is coming for them, leaving many to wonder why this didn't have closed captions. 2018's God of War and 2015's The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt both released with tiny text, but were thankfully patched with a slider to adjust this size, while 2018's Days Gone doesn't allow for any type of button remapping.

Nintendo wanted to add some more role play to its Pokémon: Let's Go! remakes of Pokémon Yellow, but the games came with mandatory motion controls, which are bad for players with physical disabilities and should never be forced. Hamilton tells me that Destiny was the first AAA console game to recognise the value in an accessibility menu, but even its makers at Bungie coloured its text a horrible yellow, against white and light blue backgrounds, for their cutscenes, creating a contrast issue.

---

Having all of the good options I've discussed in one game would be amazing, but there are many different types of disabilities, and that means many things need to be considered. Visual aspects are always going to be an issue and are an area that's seen the most improvement, yet they're still handled poorly. Subtitles are notoriously terrible in most games; and while closed captions are always helpful, good versions of these things are not commonplace yet.

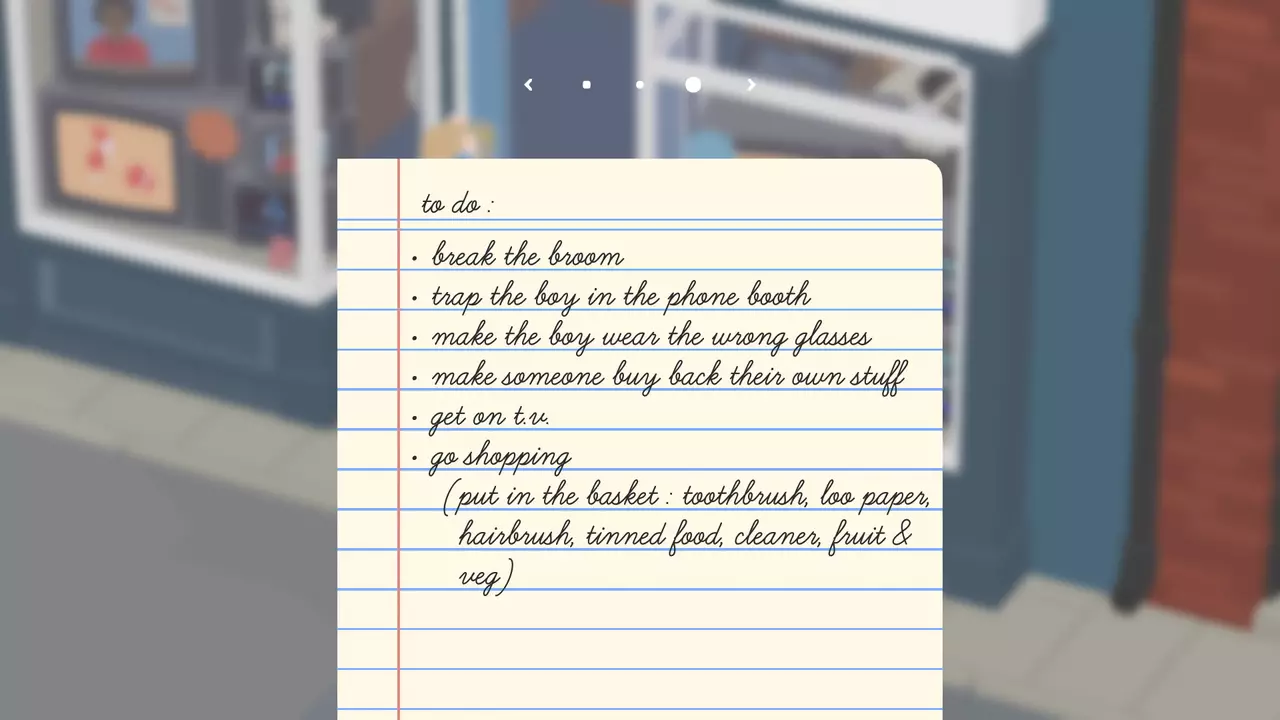

Ubisoft has collected a large amount of data showing that many of their players were turning on closed captions and leaving them on when automatic. Some games want to stand out with fancy fonts, like the recent Blasphemous, whose stylistic endeavours make the game much harder to read; while Untitled Goose Game has cursive writing on its to-do lists, which can be worse for the visually impaired (but this can be changed in the settings). Crackdown 3, John Wick Hex and The Outer Worlds all have tiny text sizes that are incredibly tough to read. Text-heavy games should also require a button press to make the story proceed, like in Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, rather than a time limit.

There are some helpful additions people may not consider, like many Rockstar games coming with physical maps, while Fallout 4 is notable for allowing the use of a Pip-Boy on another screen, both of which can be held closer to the eyes.

Some aspects of gaming cause more issues without meaning to, but newer trends can be harmful to multiple disabilities. Quick Time Events (QTEs) are a prime example of this, as they are horrible for disabled gamers. As someone who loves David Cage's games at Quantic Dream, titles like Heavy Rain and Detroit: Become Human, I've learned to accept failure and that I'll have to try and memorise the QTE sequences if I want to do well. Thankfully, Marvel's Spider-Man lets players skip these atrocities altogether.

---

More developers have begun to correct these issues when they are pointed out, to try and help those who want to play their games, patching accessibility options in or simply adjusting font sizes - but this action is usually months after release. This means disabled people have to wait, and doing this after the fact can cost the developers a lot of money. Accessibility options are therefore best handled at the beginning of a project, and are easier for developers to include if they follow the numerous disability guidelines available online, like this one.

Some developers are doing incredible things with colourblind options, but much of this push for larger accessibility is limited to the indie game sector. Big studios continue to make small mistakes, leaving simple options out.

This most likely occurs because accessibility still isn't a big conversation. When a new game comes out that raises the bar in the field it gets some attention for a few weeks, but that doesn't last. The conversation is never furthered and sites, in large, don't mention it until another game that makes advancements comes out. It isn't truly affecting the industry, especially when compared to other forms of entertainment. The biggest gaming publishers are still only doing the bare minimum - and as games make another solid push toward VR, a new set of issues looks to present themselves.

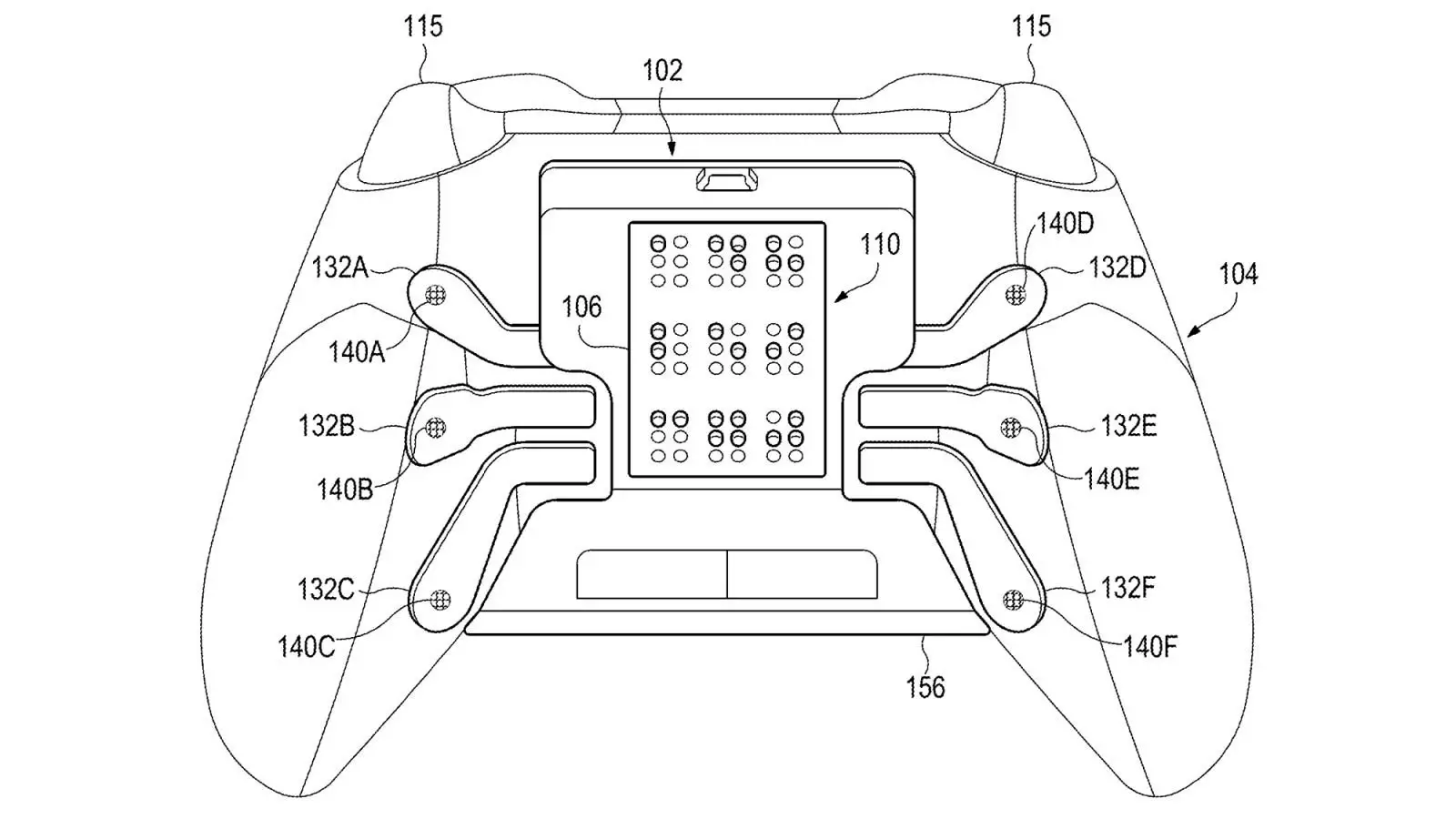

Things are looking up with developments like RAD, an auditory system allowing blind gamers to play racing games. There is also SubPac, a vest that acts as a wearable subwoofer, letting deaf players feel things that they may not hear. Microsoft is even potentially working on a controller that uses braille for their adaptive line - though it's worth remembering that a lot of companies work on patents that never see the light of day.

Whatever the future brings, it's good to know that there are still people on both sides - hobbyists and creators - working to make changes so that everyone can do what they want to: play.

---

Special thanks to Ian Hamilton for speaking with me about some of the research for this article and providing quotes. Further resources on accessibility in video games are as follows:

IGDA Game Accessibility SIG

The AbleGamers Charity (USA)

The Special Effect Charity (UK)

ACM SIGACCESS

APX

AudioGames

Can I Play That?

DAGARS

Gaming Accessibility Guidelines

Topics: Xbox, Feature, Nintendo, PlayStation