In August 2020, Yannick Zenhäusern finally got the message he'd been dreading.

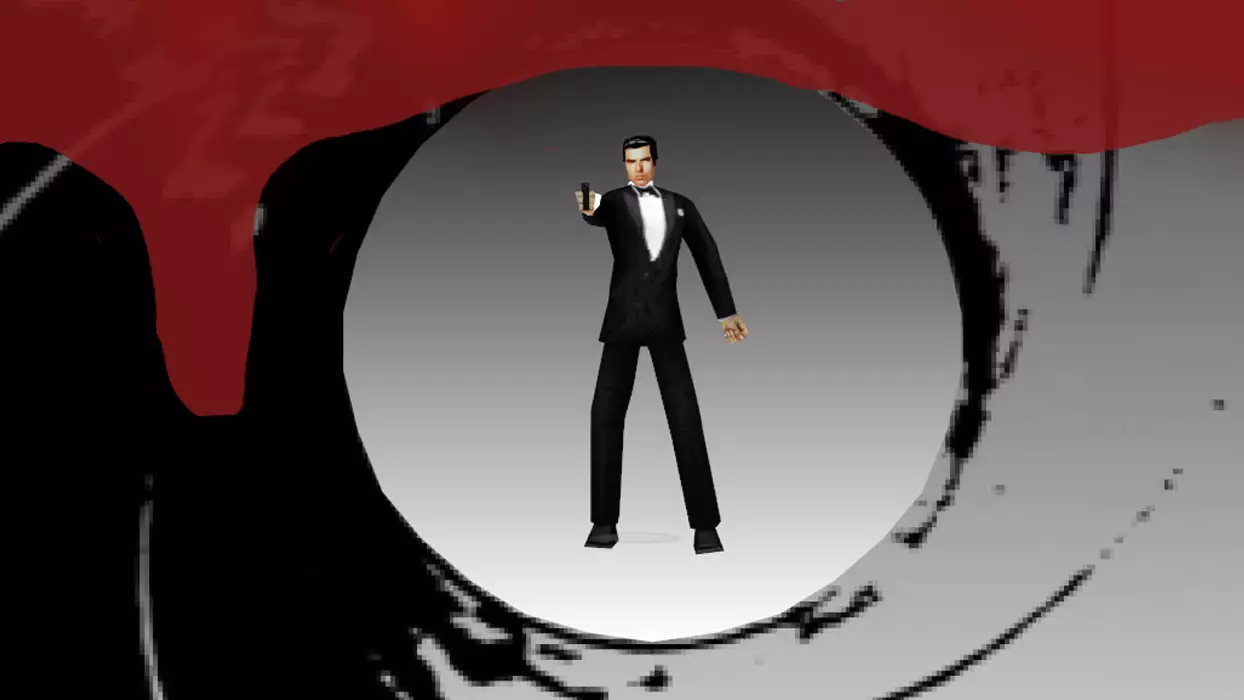

The composer's phone buzzed to life, alerting him to an urgent Twitter DM from his collaborator: self-taught 3D artist and project lead Ben Colclough. The two had spent the last few years working together on an unofficial remake of the Nintendo 64 classic GoldenEye 007, the intention being to release it in 2022 as part of the original game's 25th anniversary under the name GoldenEye 25.

The mere existence of this late-night DM immediately struck Zenhäusern as worrisome. Colclough usually communicated via Steam Chat, so to suddenly have him get in touch this way? Something was wrong. Knowing that his colleague wasn't the sort to blow matters out of proportion, Zenhäusern took the message at its word and replied immediately.

Advert

It was not good news. MGM, the company that owns the rights to James Bond, had hit GoldenEye 25 with a cease-and-desist. The project was dead, and Zenhäusern was left with one question: why would they do that?

"We always stated very clearly that we weren't making any money from it," the composer tells me via Zoom, nearly one year on from that fateful August night.

"We've been working on this for two and a half years. And first and foremost, we want this game. We want to play this game ourselves, really. So that's also another reason why we were really gobsmacked when it happened."

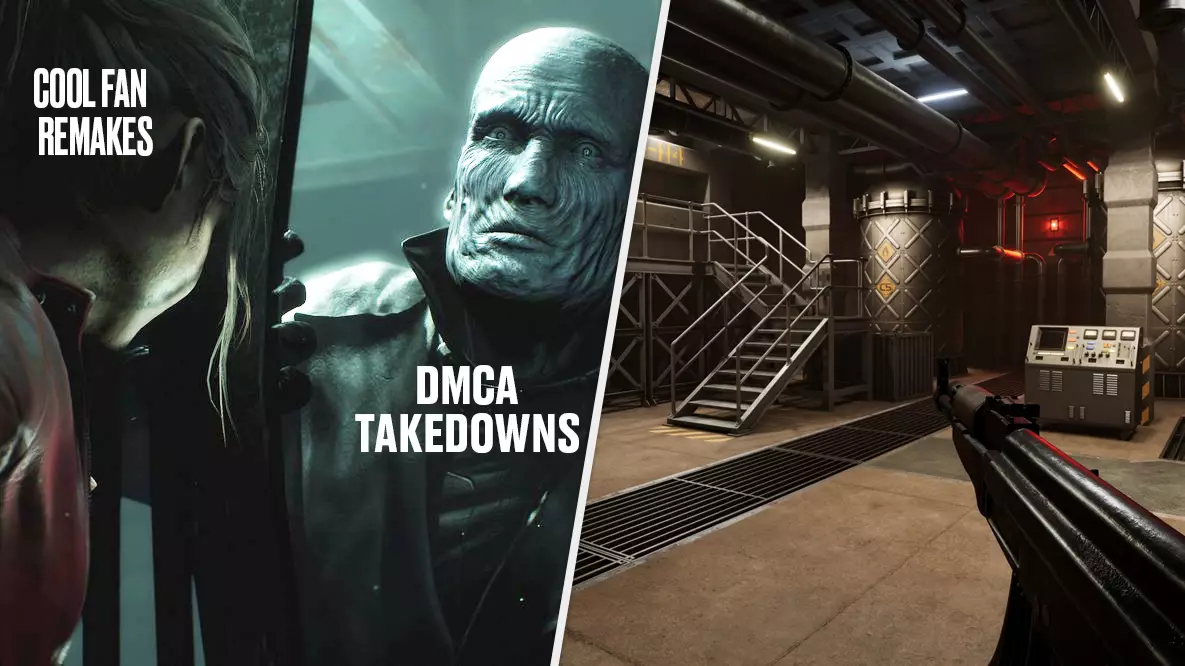

Fan-made games are, to put it mildly, a tricky business. Every now and again, a team of passionate and talented developers, designers, artists, and composers will come together to try to create their own tribute to a game or IP they love. The best they can hope for, nine times out of ten, is that the IP holder will leave them alone to release a not-for-profit build that delights fellow fans and scratches an itch. Worst case? A publisher or developer sends in the lawyers and puts an end to all the hard work.

Advert

Zenhäusern and the rest of the team genuinely believed, at least for a while, that GoldenEye 25 would fall into the former camp. The composer had previously worked on GoldenEye Source, a popular total conversion mod of Half-Life 2 that transformed Valve's FPS into a popular online remake of GoldenEye's much-loved multiplayer. Source had been allowed to continue since its inception all the way back in 2005, so when Zenhäusern was approached by Colclough two and a half years ago with the idea of remaking the single-player campaign for the 25th anniversary, both assumed it wouldn't be an issue.

"We thought maybe MGM would accept these sorts of things when it's made clear that it doesn't yield any money," Zenhäusern tells me. "And especially after years of development and plenty of news coverage, we thought someone must have got the hint that we're working on something."

As with a lot of fan remakes with promise and talent behind them, GoldenEye 25 received a lot of attention. Eurogamer, GAMINGbible, PCGamesN, and many more outlets covered the in-development project and praised how well it was coming along. From this writer's point of view, it's great to shine a light on projects like GoldenEye 25 - projects that we know will resonate with an audience who have been waiting to see something just like made official. This, of course, also brings with it the risk of the wrong kind of attention - specifically, lawyers wielding cease-and-desist orders.

Advert

Having covered my share of fan projects in the past, I ask Zenhäusern whether it truly helps or hinders to have the media involved. After a pause, he tells me he thinks the benefits of the press outweighed any potential risks.

"We were more pleased in terms of the coverage, though we were typically a little nervous when a new article came out," Zenhäusern explains. "At the same time, it made us feel a little more safe, because we knew nothing happened. I can't play down the benefits that we had from that."

At a certain point, however, even the most high-profile fan projects have to accept that they're not untouchable - no matter how positive things are looking. Metal Gear fans may well remember the infamous case of the Outer Heaven's ambitious 3D remake of the original Metal Gear that was shut down by Konami back in 2014. This particular cancellation had an unexpected sting, given that the team working on the project insisted that it, at one point, had the approval of Konami itself, not to mention the involvement of Snake voice actor David Hayter.

Advert

Project lead Ian Ratcliffe tells me over email that he'd only been involved with the Metal Gear remake for a few months, but that receiving the cease-and-desist from Konami was a genuinely unexpected blow. Wisely assuming that it would only be a matter of time before Konami found out about the project, Ratcliffe decided to get in touch with the publisher to let it know what he and his team were doing, to ask if it was going to be a problem.

To the immense surprise of Ratcliffe, they were given the green-light - provided nobody would make any money from the project. They were also told they could use any existing assets, which Ratcliffe took as the "golden ticket" to go full steam ahead. With Konami seemingly in their corner, huge interest from the gaming press, and David Hayter himself emailing to ask if he could help out (Ratcliffe asked the actor to meet via a Skype video call so he could verify it wasn't someone taking the piss), it seemed the long-awaited Metal Gear remake was to be made by fans, for fans.

"To my knowledge, it was Konami UK that first got wind of it," Ratcliffe explains. "They were very supportive throughout the whole process, especially Jay Boor (former Konami PR, now at Kojima Productions), who was the person I mainly dealt with.

"I remember Jay calling me one day to say that 'Japan' has heard of the project and that an overnight meeting was going on and that we had to halt the project until said meeting was over. We all thought that that was the end of the road for us. The next day I got a call saying that we could go ahead with the project, so we were all thrilled."

Ratcliffe later learned that this meeting was with Kojima Productions. It was Hideo Kojima's team, not Konami, that had approved the project. Unfortunately, it seems it was Konami that ultimately got the final word.

Advert

"A few weeks went by and I got another call from Jay," Ratcliffe tells me. "Another meeting was being held, only this time the heads of Konami Japan were involved. It was those guys that pulled the plug. Apparently they couldn't make sense of why we wanted to create a project as big as Metal Gear for zero profit. And that was the reason they pulled the plug."

Where do these projects go after years of work and effort is seemingly flushed down the drain in an instant? For Ratcliffe and the team, the blow to morale was too great. There were tentative plans to recycle what had already been made into a new and legally safe IP, but the burnout among the team, coupled with a relative lack of enthusiasm from the community, killed it dead. Everybody wanted a remake of one of the most iconic PlayStation games ever made - nobody had signed up for a new IP that was only sort of like Metal Gear Solid.

"I guess we were all just pretty burned out after everything that happened," Ratcliffe admits. "We said we would all get back to it one day, but that day is still yet to come unfortunately."

Fan-made games can, of course, find new life after being shut down. Some years before Capcom released its own remake of Resident Evil 2, a small team by the name of Invader Studios - then known as InvaderGames - was developing an unofficial and unapproved remake of the 1998 classic called Resident Evil 2 Reborn in Unreal Engine 4.

Capcom consulted with InvaderGames and the project - which was already pretty far along - was shut down. No doubt this was because Capcom already had its own Resident Evil 2 remake in development. You have to wonder if Capcom might have been a little more lenient with the project if it hadn't, especially given the fact that the company invited InvaderGames to meet with them and discuss the matter properly.

Given that most publishers and developers don't do much more than throw out a harshly worded cease-and-desist, InvaderGames came away from its experience with Capcom feeling as good as it could. It's an IP-holder's absolute legal right to put a stop to any fan projects of course, but given the amount of love and passion that clearly go into them, it couldn't hurt for the process to be a little more gentle.

In the case of Resident Evil 2 Reborn, InvaderGames was energised to retool the project. After some work, it ultimately became Daymare 1998. Released in 2019, it didn't do quite as well as it might have done if it was the Resident Evil game it was intended to be, but it was a hit with fans and critics who longed for a vintage survival horror experience nonetheless.

Unbowed, Zenhäusernand and Colclough are taking a similar approach with GoldenEye 25. Development on the project has shifted, re-working what has already been developed to deliver a game called S.P.I.E.S., a Rare-inspired '90s FPS. Much like Daymare 1998 found its own identity, it's Zenhäusern hope that S.P.I.E.S. doesn't need to be related to James Bond for players to get something out of it.

"It's going really good," Zenhäusern tells me of this new chapter in the game's development. Even before GoldenEye 25 was shut down, he and Colclough had been repurposing various bits and pieces, just in case. "I started to work on some thematic material, you know, some of the music, some of the sound effects. And Ben was already starting to repurpose objects and levels and so on.

"There are still many things in it that resemble GoldenEye, and so I truly think people that know GoldenEye and love it for what it was, will almost certainly love S.P.I.E.S.. The music sounds very much like James Bond - and that was done on purpose. Also some of the levels, how they're being handled, and so on. There's a lot of callbacks to GoldenEye."

Transforming GoldenEye 25 into S.P.I.E.S. also gives the team a chance to try new things - things they wouldn't have been able to do with a faithful recreation of Rare's game. Zenhäusern excitedly tells me of the new weapons, characters, and levels that have risen from the ashes of the Bond license. It's a lot more work, certainly, there seems to be a real sense of positivity around the new direction.

Despite this, Zenhäusern is frank with me when I ask if he thinks GoldenEye 25 giving way to S.P.I.E.S. will end up being a blessing in disguise. "I would have preferred to finish GoldenEye, to have that, and then go to S.P.I.E.S.," he tells me. "That was the plan in the first place: GoldenEye first, then our own thing. Now we've taken the shortcut, so to speak."

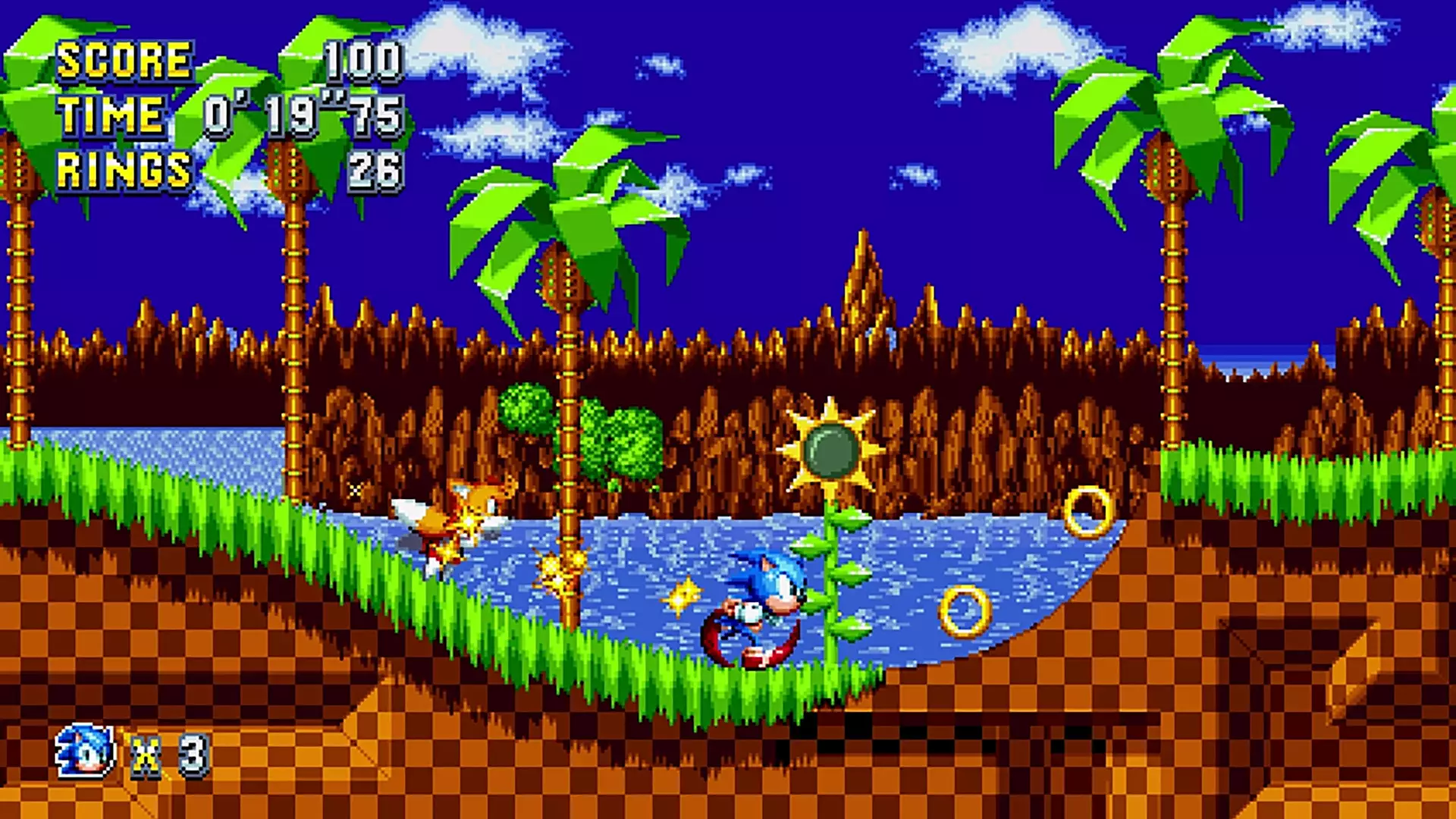

At this point you may well be asking yourself why so many developers still try to get fan projects off the ground. Metal Gear Solid, GoldenEye 25, and Resident Evil 2 Reborn are just a few examples in a long line of doomed remakes that should serve as a stark warning to any would-be fan games. There have been success stories, sure - Sonic Mania and Black Mesa are just two shining examples - but at a certain stage, aren't these developers just setting themselves up for heartbreak?

For Ratcliffe and Zenhäusern, the "why" of it all has an easy, obvious answer: the remakes they were working on were games they genuinely wanted to play themselves. They had the knowledge, the ability, and the contacts to really get cooking, and they gave it their best shot.

"I really enjoyed the experience," says Ratcliffe. "We had support from a huge amount of people in and outside of the industry. It was a good feeling having those people behind us. My emails were blowing up on a daily basis with fans asking about the project and wanting to get involved. We had developers from Ubisoft and Sony's XDev who began to help us towards the end of the project. We had professional voiceover artists that worked on franchises such as Final Fantasy and Call of Duty. A guy from Sony Music Publishing even approached us about providing the soundtrack! Then on top of that we had literally every gaming news outlet wanting to do a piece on us. It was crazy how far the project reached.

"After the project was shelved I actually received a job offer from someone who was hiring on behalf of 2K Games. Sadly I never believed in myself and didn't turn up for the interview, so I always look back on that period of my life and wonder what could have been."

Should developers like Ratcliffe and Zenhäusern have been allowed to continue with their work, no questions asked? For fellow fans, the answer is obviously an emphatic yes. But it's also completely understandable that the owner of an IP might be a little funny about someone outside of their control using characters that they intend to use for their own commercial purposes going forward. Nintendo, for example, is infamously protective of its stable of classic characters. That, of course, is exactly why it shuts down any and all fan-made projects faster than you can say, "Ocarina Of Time remake."

I submit that it would also be entirely reasonable for any company to send in the lawyers if somebody was profiting off their property without their permission. That probably goes without saying. Similarly, it's probably fair to back any publisher shutting a fan project down if that project was a gross misrepresentation of the source material that could damage the brand. You couldn't really fault Nintendo for shutting down a game with a name like Mario Sex Party or Link's Shotgun Adventure, could you?

But what about when a team of hardworking fans has no intention of making money from the game, and has approached the material with nothing but respect and care? Those are the kinds of games Zenhäusern and Ratcliffe were trying to make. They knew how much the fans wanted these games, because they were those fans.

Zenhäusern truly believes GoldenEye 25 should have been allowed to continue, even if that involved his team working more closely with MGM. "It would be easy money for the company," he tells me. "So I really don't understand why they don't do it." There's much the composer can't legally tell me because of the cease-and-desist, but he does add that there were "attempts" made to salvage the project with MGM. Ultimately, Zenhäusern was left with the impression the company had no intention of reviving GoldenEye - either alone, or with the help of fans.

There are companies that allow fans to work on fan-made games so long as they stay within set parameters, including not making a profit or using characters for anything wildly inappropriate. SEGA has long been considered the gold standard within the industry when it comes to embracing fan projects.

Back in 2016, the creator of Sonic fan-game Green Hill Paradise Act 2 was thrilled when the official Sonic The Hedgehog account gave them the thumbs up, telling all fans of the blue blur to "keep making great stuff". As recently as this year, SEGA of America's social media and influencer manager Katie Chrzanowski reiterated that fan games are welcome and almost always fine, provided no money is being made. Valve and Square Enix have also proved to be relatively accommodating in the past, but it's still rare to see. If only more companies were willing to follow these examples, especially with fans who are clearly comfortable doing things by the book.

"We wanted to be transparent and, and let people see the progress," Zenhäusern says, before musing that it may have been better to work on the project in secret and then release it. "But then again", he concludes,"it's still illegal... So it's not better."

For now, the process of developing fan games remains a heartbreaking and uncertain one. There are no guarantees, no promises, and there's always the constant, creeping fear that it can all come crashing down with one phone call. Even so, I'm left with nothing but the utmost admiration and respect for Zenhäusern, Ratcliffe, and every other fan out there willing to put everything they have into building something special for their fellow gamers with no guarantee of success or reward.

Having been through the process, what would Zenhäusern say to fellow fans with dreams of bringing back a classic IP with their own two hands? "Do your own thing," he says. "Take plenty of influences, but do your own thing. You want to be legally safe. It's not that hard. There are enough people out there nowadays who can write decent stories, who can write decent characters. Try to take it from there and not make it too ambitious a project."

Ratcliffe is a little more optimistic. This could well be because his own fan project was shut down years ago, while Zenhäusern ordeal is still quite raw, but it's clear he remains a firm believer in the importance of fan games.

"Fan games keep the franchises we love alive," Ratcliffe tells me simply. "Look at the state that Metal Gear is in now for instance, with Kojima gone. We may never see another Metal Gear game again. It's a pretty sad thought, really.

"My advice to anyone thinking about doing their own fan project? Grab it with both hands and run with it. At the end of the day, you never know what might happen. Even if the project gets shelved, you may still find your way into the industry."

Featured Image Credit: Capcom/Ben Colclough/Yannick ZenhäusernTopics: Feature, GAMING, Resident Evil, Nintendo, PlayStation, PC, Capcom, Metal Gear Solid