The imminent closure of the online stores for the PlayStation 3, PlayStation Portable and PlayStation Vita will see a number of games simply disappear from existence. By confirming that the PSP and PS3 stores will be shuttered on July 2, and the Vita store on August 27, Sony is saying goodbye to around 2,200 titles, including (as reported by VGC) 138 that only exist on those outgoing digital storefronts. This 138 includes the notable likes of Tokyo Jungle, Rain, MotorStorm RC, and Infamous: Festival of Blood. (Note that if you already own games on these stores, they will remain downloadable after the closures.)

And that can't be right. Whatever the quality of these games that are about to vanish for good, surely no lover of video gaming wants a title that people worked hard on to become completely unavailable, anywhere? This action from Sony is hardly unprecedented, as games go out of print, and out of circulation, all the time. But, can't something be done to better preserve the history of the most popular and most exciting entertainment medium on the planet?

Article continues after the video below

Advert

---

Watch our documentary on 25 years of the Pokémon Trading Card Game

---

Advert

Iain Simons certainly thinks so. As the Director of Culture at the UK's National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, he's part of a team that wants to make the history of video games accessible and understandable by everyone, be they a committed gamer or a fairweather player. "We're nothing if not ambitious!" he tells me, when I ask him about the situation with Sony's online stores, and the issue of preservation in the gaming medium.

"Historically, games haven't really considered themselves as being a cultural industry," Iain explains, when I ask him why video games are so bad at preserving their past, compared to the likes of movies and music. "It's literally baked into their business model that the next game is always the most exciting one, the one you really need to have - and that the previous one is now obsolete. With that underpinning everything, it's easy to see why preservation isn't top of the list of priorities."

It's hardly uncommon for someone whose first introduction to a series like, for example, The Legend of Zelda, is a very recent release, and for them to want to dig back through the franchise's history, exploring previous titles to trace a path from its debut to the here and now. Zelda is a series that's incredibly well supported by Nintendo, of course, with games from the 1980s just as easy to (legally) play today as the latest Switch offering. It's not a tough one to play everything in, save for a few niche exceptions.

But what if you were introduced to Sucker Punch Productions by their 2020 release Ghost of Tsushima, and wanted to play everything they'd put out before? That'd take you back to the studio's Infamous series, and to Festival of Blood, a standalone expansion for Infamous 2 released in 2011. And a game that's about to be wiped from the face of PlayStation history.

Advert

"It's a business!" Iain responds, when I ask if Sony has any responsibility to keep a title like Festival of Blood available for players. "Sony, or indeed any other publisher or developer, has no responsibility to maintain access in perpetuity. The discussion that needs to happen is around platforms and developers working with heritage institutions to find a way to make it possible for their work to be legally preserved. That's not just about software of course, but hardware, too."

No doubt there are readers out there now thinking, well, I've got loads of old games backed up, thousands of them, thanks to any number of emulators able to run ROMS of titles from right across the gaming spectrum - from early home computer games right up to Xbox and PlayStation hits. But that's a legal and moral grey area, to say the least - not that we don't have a guide on how to best revisit certain classic consoles, right here.

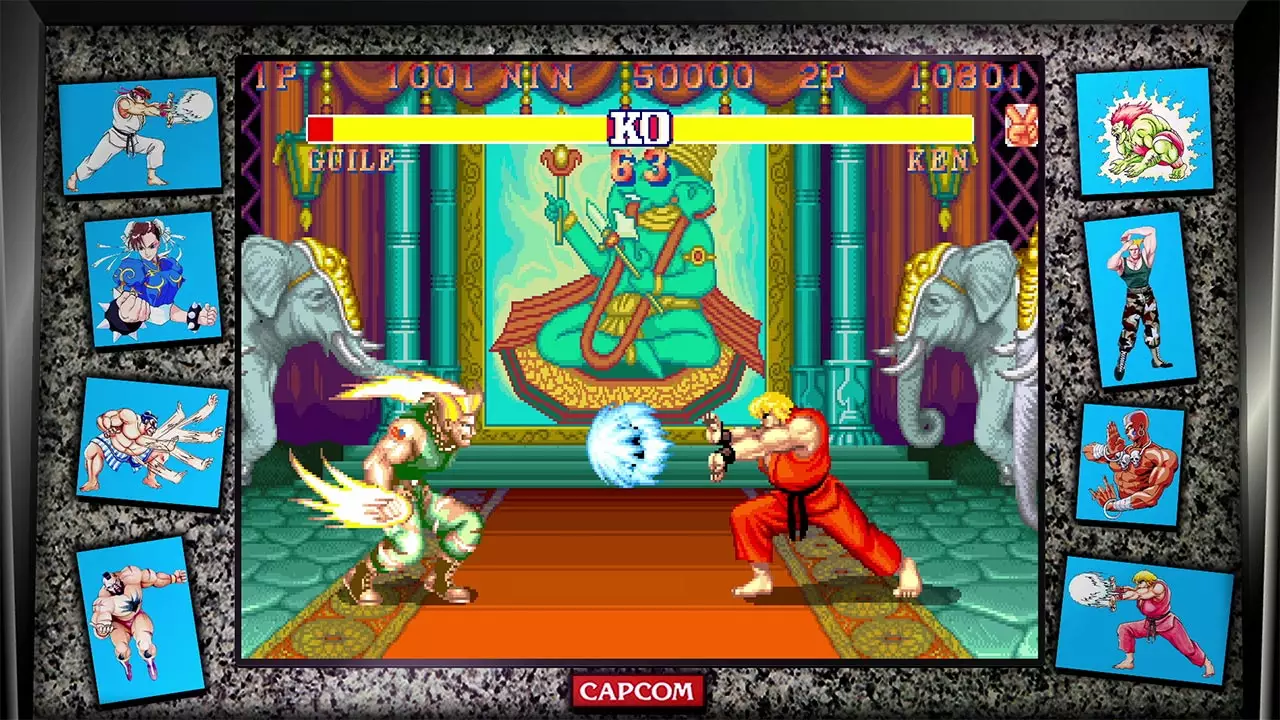

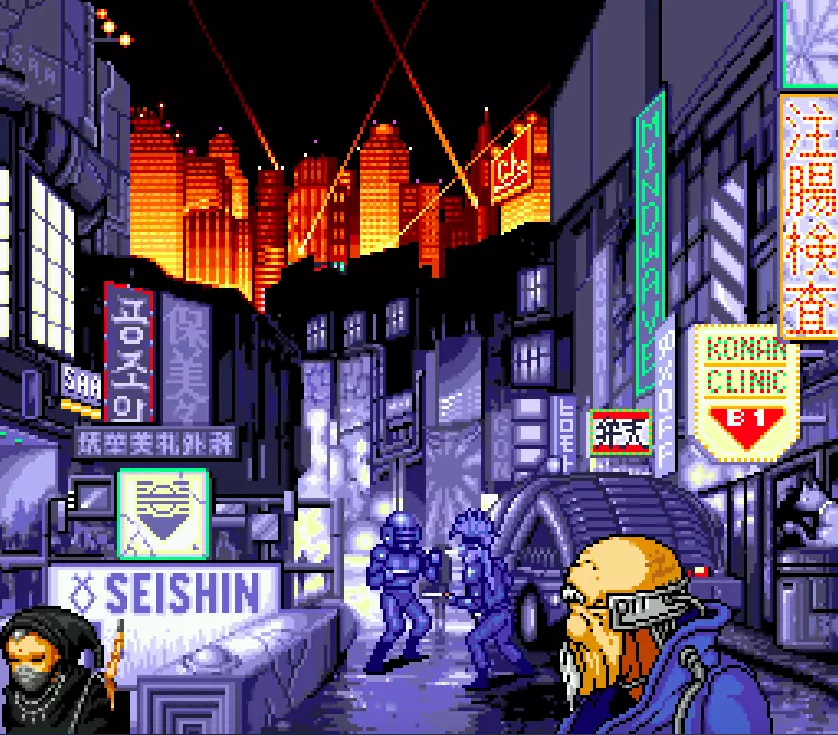

There are, of course, many above-board ways to play old games, too - mini-consoles based on old SEGA and Nintendo systems continue to be popular, fully licensed platforms like the Antstream Arcade streaming service (imagine Game Pass, but, retro) and the handheld Evercade are building their audiences, and publishers like Capcom, SEGA, SNK and Konami have released excellent compilations, covering franchises like Castlevania, Mega Man, Street Fighter and Contra. But piracy can't really work hand-in-hand with proper preservation, says Iain.

Advert

"Piracy is unequivocally wrong and cannot be part of any formal preservation effort," he says. "However, we can't pretend it doesn't happen. In fact, given that our interest is in documenting the complex histories of video games culture, game development and the games industry, researching and telling the stories of piracy is key to developing our understanding. For that reason, piracy and its impact and consequences is certainly something we want to research and invite our visitors to think about."

I've personally long-hankered for a particular game of my teenage years to become available again - the 1994 Mega CD version of Konami's Snatcher, a cyberpunk-themed graphic adventure game directed by Hideo Kojima that I chose not to buy when offered it for about £30, back around 1996 or so. As the only English-language version of the game, original copies now sell for eye-watering amounts on the second-hand market - and yes, I continue to kick myself. Realistically, the only way I can play it today is by pirating it. But the lack of a re-release in the years since could be down to one simple thing: my own sources tell me Konami simply doesn't have that code, anymore.

Sounds ridiculous, doesn't it? But Iain can understand it. "Historically, [games get lost] mostly because there's simply no process in place to keep and preserve materials. Studios move onto a new project, and archives have been gradually lost. Many games from the 1980s were developed very quickly with little or no design documentation, and we've even heard stories of entire archives of floppy disks being thrown away in office moves because they were thought to be trash!"

Advert

He adds that studio bankruptcies have seen materials simply thrown away - and that the National Videogame Museum has actually recovered items, in the past, from such instances. But the NVM is more than just a place to see old games and systems to play them on, as Iain explains.

"The work we're doing at the NVM and British Games Institute (BGI) isn't out of nostalgia. It's out of a concern for the future. We want to be able to inspire and educate new kinds of game-makers to make new kinds of games. It's important to understand how big a job this is though, and we definitely aren't the only people trying to do it. We work with lots of other museums and collectors around the UK and the world."

One cooperative scheme the NVM is involved in right now is the Videogame Heritage Society, alongside the likes of the British Film Institute and the Cambridge-based Centre for Computing History (who I also reached out to for this piece, but sadly they were unable to contribute in time), as well as private collectors. Launched in early 2020, the VHS is, says Iain, "designed to bring together all those involved with games preservation".

And perhaps it's schemes like that VHS that offer the most hope when it comes to video game preservation beyond the shady stockpiling of ROMs. Because if a massive platform holder like Sony isn't going to do it (and isn't expected to), and huge gaming companies can just lose their content completely (and will continue to do so), it's on everyone else to play their part in ensuring we don't see hundreds and thousands of video games blink out of existence, when they could have been saved.

Thanks to Iain and also Conor Clarke and Michael Pennington at the National Videogame Museum. Find the museum online here. Related: check out our list of the greatest handheld consoles, ever.

Featured Image Credit: Konami, Sony Computer Entertainment, Sucker Punch Productions

Topics: Sega, Konami, PlayStation 3, Nintendo, PlayStation, Capcom, Interview, Retro Gaming