To a lot of video game fans today, Japanese developer Hideo Kojima is just about inseparable from Metal Gear Solid, the Konami-published, Solid Snake-starring stealth-action series that was kickstarted properly in 1998 by the eponymous game on the original PlayStation (a game which may be in line for a remake). But just as the man has kept himself busy in the years since Metal Gear Solid, not only with several sequels but most recently with 2019’s Death Stranding via his independent Kojima Productions studio, he didn’t begin his career in the era of the PS1. Far from it, indeed: Kojima’s work in games goes back to the mid-1980s.

And yet, there’s a connection of a kind to be drawn between Kojima’s most recent title, where the player must do all they can to keep a digital Norman Reedus balanced and upright over tricky terrain, and his very first. While initially keen on a career in film having made some short movies of his own - including a zombie film that he sold tickets for at his school, as he told The Guardian in 2012 - Kojima joined Konami in 1986 and almost immediately got stuck into production work on a game that offered rather more weirdness and deeper gameplay than its cutesy art suggests.

Watch the trailer for the 2021-released Death Stranding - Director’s Cut below

Penguin Adventure, or Yume Tairiku Adobenchā, was released in October 1986, when Kojima was 23 years old, for MSX computers. In it, the player controls Penta, the penguin of the title, as they race forward ‘into’ the screen (Space Harrier style) collecting fish and dodging holes in the ground that will unbalance him, knock him down, and cost precious time. While there are also enemies as stages progress, and some bosses you'll have to send plummeting to their doom, the biggest challenge can be the ever-ticking clock, which so easily runs down before Penta’s reached the level’s finishing, um, statues? It’s not a line, more a spot for Penta to have a well-earned rest, and maybe even a beer, before his next sprint.

Penta’s quest - ultimately to find a restorative, magical apple to save a penguin princess and bring order to the Penguin Kingdom - is made easier by a handful of shops, where Inuit-styled salesmen will flog you various power-ups, including a gun because video games. The problem is that these secretive stores are disguised as regular obstacles, so Penta will have to fall down a few holes before finding the right ones (or rather, the small ones). The currency of choice? Fish, obviously, so it’s advisable to catch as many as you can that are flung into the air during the course of a stage - and you can gamble them to increase your spending power. And said stages go beyond the expected water and ice affairs - Penta also explores caves, forests, and even the very edge of our atmosphere if you grab some magical wings.

While the game ends with a strange message from Konami - “We promise to continue sending romantic game messages” - the credits of Penguin Adventure don’t actually feature Kojima’s name beside that of the likes of designer Ryouhei Shogaki and co-director Hiroyuki Fukui. Instead, his involvement in the game, as an assistant designer, has only really come to light in more recent years. After Penguin Adventure, Kojima worked on Lost World, apparently set on the Titanic, but that was abandoned as Konami felt it was too ambitious for the MSX. What wasn’t, however, was the game Kojima made next.

Advert

I don’t want to dwell all that much on Metal Gear, the first game Kojima directed, as 1987’s top-down stealth-action game for the MSX, later reworked without his involvement for the Nintendo Famicom (and NES, internationally), lays the foundations both gameplay and storyline for Metal Gear Solid. It’s the beginning of Kojima’s fame, albeit some time before he’d achieve substantial recognition in the West and ultimately become one of the few games developers who people just might recognise on the street. But it’s worth noting that the game that became Metal Gear wasn’t dreamed up out of nowhere by Kojima alone.

---

“Once we got a working build running, and they saw that exclamation mark pop up when the enemy gets surprised, that sold them on the concept. They all changed their tune.”

- Kojima recalls the moment Konami bought into Metal Gear

Advert

---

A war game was already in development at Konami, albeit subject to several false starts over the course of some two years, and when it found its way to the young Kojima, he wondered how it could be adapted for something more like The Great Escape. His idea was met with “passive-aggressive resistance,” he told Nice Games magazine in 1999. “I was ready to quit Konami altogether,” he continues, but after further conversations attitudes began to change, and a now-famous gameplay mechanic sealed the deal: “Once we got a working build running, and they saw that exclamation mark pop up when the enemy gets surprised, that sold them on the concept. They all changed their tune.”

Metal Gear was, as history shows, a success, and received a Kojima-directed true sequel in 1990, Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake, again for the MSX. (This isn’t to be confused with Snake’s Revenge, an alternative sequel released outside of Japan for the NES - the story goes that when Kojima learned of this sequel, “through rumours, initially”, he was encouraged to make MG2: SS, although he doesn’t consider Snake’s Revenge to be a bad game). But before Metal Gear 2 came something altogether more, well, cinematic, I suppose. A game that went some way to realising Kojima’s earlier hope that games could deliver “film-like experiences”. In late 1988, Konami released the Kojima-directed cyberpunk detective game, Snatcher.

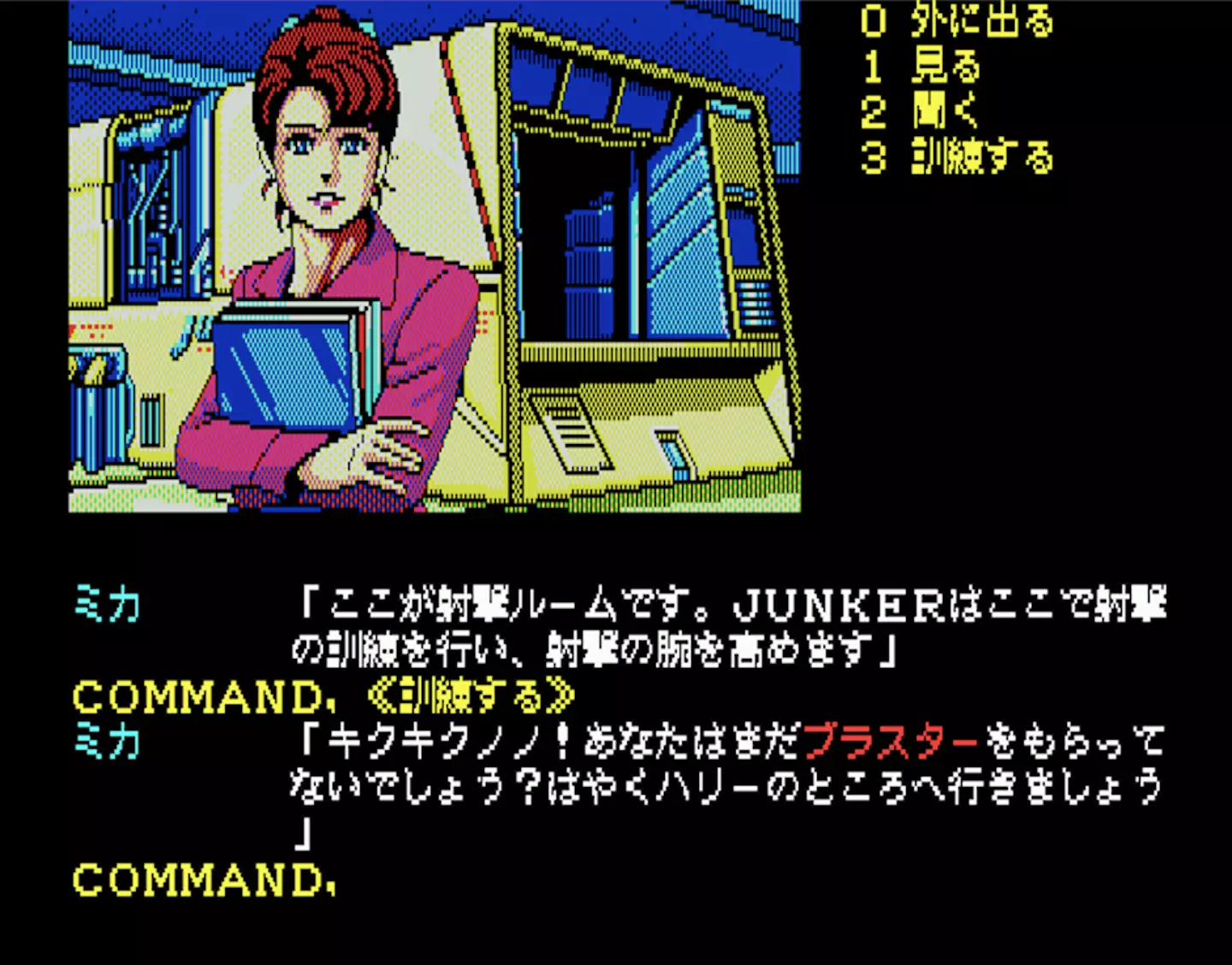

Snatcher is a game I talk about a lot, perhaps too much - just ask my colleagues, who I’m sure will never play it, so sick are they of hearing about it. But then, we all like to rave about our favourite things, don’t we? So I have done, on these very pages, before now - here, here, and here. Mixing anime-like visuals with a text adventure interface - all “look” at this, “move” towards that, “investigate” this suspicious-looking picture on your boss’s wall, surely he’s not involved here, unless - Snatcher is Kojima channeling Blade Runner, Akira, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and The Terminator. Its very serious near-future story of human beings in the city of Neo Kobe being killed and replaced by humanoid machines wearing lookalike skins is balanced by a healthy dose of goofy humour and playful mechanics within its limited interface.

To have gone from the very 8-bit Metal Gear to this exploration-rich, narratively engrossing adventure in a cyberpunk-styled city of striking sci-fi imagery and mature themes was quite the leap. But Snatcher didn’t connect with the West until much later, via 1994’s one and only English translation of the extra-chapter-added PC Engine CD version of the game, released on SEGA’s Mega CD add-on for the Mega Drive. And “connect” is perhaps overselling things - Snatcher sold poorly on SEGA’s already aging hardware, only shifting “a few thousand copies” according to its translator Jeremy Blaustein, who told the NeoKobe.net site: “I know the SEGA CD (Mega CD in Europe) and had no software for it, but where was everyone when Snatcher came out? Boy, was that embarrassing, having it fail so badly.”

Advert

---

“I created Snatcher entirely by myself. I could control the timing of sound effects, where fade-outs occurred, and pretty much everything. I was the only person on the development team who fully understood how it all fit together.”

- Kojima recalls his role on Snatcher

---

Advert

Snatcher’s super-limited availability, and Kojima’s substantially greater profile, has seen the original Mega CD version of the game trade hands for eye-watering sums on the second-hand market. Some might argue it’s worth the asking price as much for what it represents in Kojima’s career as the game itself (which is very good, indeed): the first time he really cut loose as an individual, and did everything his own way. Speaking with Nice Games in 1999, he said: “I created Snatcher entirely by myself. I could control the timing of sound effects, where fade-outs occurred, and pretty much everything. It meant that I was the only person on the development team who fully understood how it all fit together.”

Six years earlier, before Snatcher came West, Kojima spoke about his feelings on the game, having seen the expanded PC Engine version sell reasonably well for the platform. Speaking to an unknown publication but preserved at shmuplations.com, he said: “My concept for Snatcher was not to make a game with a broad and shallow appeal that anyone, ‘from children to adults!’ could enjoy. The concept was different: this game would appeal to, and remain etched in, the heart of a very specific kind of person.” And accepting criticism that the game leans on the likes of Blade Runner for its world building and plot, he continues: “What I was interested in expressing was not an original story or world. The world was simply the empty vessel for the activities and lives of the various characters that you meet, and the inexorable fate that they are dragged into unawares… I wanted to present that experience, which can only be adequately conveyed in a meaningful and satisfying way through interactive media. In whatever shape or form it takes, that is the kind of game I want to make again.”

And guess what: he did make that kind of game again. Following the MSX2’s Snatcher spin-off SD Snatcher - the top-down role-player with super-deformed visuals did actually inform the expanded release of the original game, inspiring the third chapter included on PC Engine and Mega CD - Kojima worked on Policenauts, which released in 1994 for PC. Later ported to the SEGA Saturn, 3DO and Sony PlayStation, Policenauts walked a comparable path to Snatcher - it’s a beautifully drawn graphic adventure game, where you play a former astronaut turned detective living in a Los Angeles after losing 24 years to cryrosleep - but didn’t follow it West, remaining a Japanese exclusive title until fan translations took it to a broader audience, the first arriving in 2009. And like Snatcher, it’s an older, pre-Metal Gear Solid Kojima game that there’s a great demand for a rerelease of, having attained a great level of cult appeal - English-translation double-pack when, Konami?

Advert

And like Snatcher, Policenauts mixed some super-detailed scientific research and heavyweight themes - organ harvesting foremost amongst them - with a degree of comedy that hasn’t held up so well. The protagonists of both games - Gillian Seed in Snatcher, and Jonathan Ingram in Policenauts - have a tendency to objectify the women NPCs they meet, and Ingram can even, well, kinda grope certain characters, with ‘wobbly’ animations included. It’s an unfortunate, distinctly outdated footnote in the story of an otherwise excellent game - and something that’d surely be removed from any reissue or, dare we dream, remake.

---

“I’m trying to create a game that will have a small but positive effect on players’ actual lives.”

- Kojima reflects on his work in the wake of Policenauts

---

Speaking about Policenauts in 1996, in an interview preserved by GLSA, Kojima said: “I’m trying to create a game that will have a small but positive effect on players’ actual lives. I know it sounds a little dramatic, but that’s what I’ve been thinking about for a long time now.” But he was also quick to draw a line between movies and the cinematic style of both Snatcher and Policenauts: “I wasn’t trying to use the format of games as a vehicle for movies or anything. Rather, I feel that what the game industry lacks right now is the quality of lighting, acting, and direction that you find in movies. Then there’s the depth of the story, the accurately depicted relationships, and the final polish of your story… I think it’s incredibly difficult to make a game that matches the production quality of a movie. Policenauts uses cinematic camera work and cuts, and it was my awareness of movies that caused me to use those techniques.”

Today, to play Metal Gear Solid V, or Death Stranding, is to witness a game developer operating on the edge of movie production processes. The long cutscenes, the complex and interwoven plotlines, the starry casts: there’s no denying that Kojima (still) harbours ambitions of directing motion pictures. Kojima Productions has stated its intent to create films, and in November 2021 opened a Los Angeles studio specifically to focus on this area. So while there are gameplay connections to be drawn between the slippery stages of Penguin Adventure and the cross-country careful-where-you-step progression of Death Stranding, all of these movie-influenced elements can be traced back to Snatcher and Policenauts - games that, really, deserve another chance to shine in the present day (oh look, here’s another piece of mine, on that very subject).

That decision is out of Kojima’s hands - he left Konami in 2015 - but in the wake of aesthetically comparable commercial successes like Cyberpunk 2077, and given Kojima’s status today as one of gaming’s most-revered creators, it’s not impossible that someone, somewhere, won’t resuscitate these landmark adventures, even if that’s just as remasters. Penguin Adventure, on the other hand? Yeah it’s fun for ten minutes if you can play it, but not every chapter of Kojima’s career is worth revisiting.

This piece is part of a series profiling influential game creators, true masters of style, and their key works. Read previous entries: Fumito Ueda (Shadow of the Colossus), Amy Hennig (Uncharted), Hideki Kamiya (Devil May Cry).

---

This editorial content is supported by Philips OneBlade. Philips is committed to providing products that fit into every individual's life, to suit every personality's idea of style. Every one of us is unique, and every one of us feels comfortable and confident in different ways - and the flexibility of Philips OneBlade ensures that anyone can express themselves in a way that's all about them. Find more information here.

Featured Image Credit: Konami, Hideo Kojima on TwitterTopics: Konami, Retro Gaming, Opinion, Philips